Constructions made of iron will

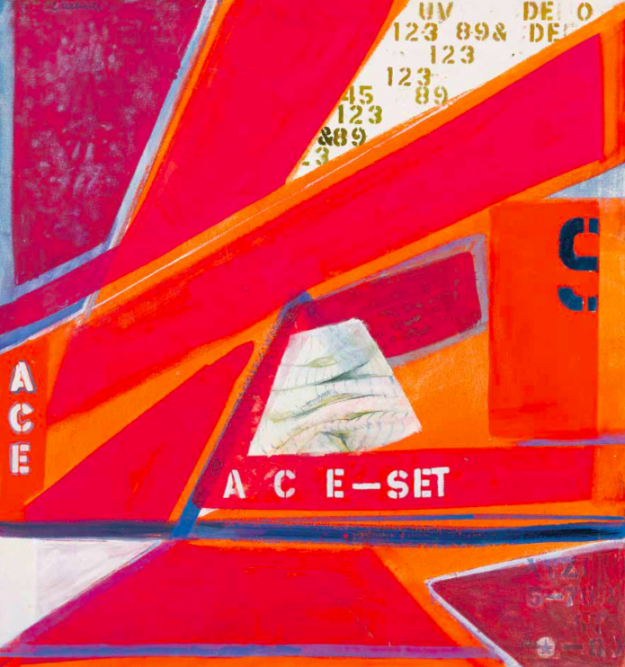

The painting in front of me is Messenger (1973) by Elena Urbaitytė (b. 1922). The Lithuanian version of the title means a person who brings a message. I decided to check the actual meaning of the word, because I doubted the accuracy of the translation. According to omniscient dictionaries, this same word could have been translated in several different ways. The word messenger in English means not only the one who brings a message, but also an envoy, herald, courier and even a challenger, which is an ancient concept that is part of Lithuanian culture. The translation of the title into Lithuanian is not quite accurate, thus it seems that I will not be able to make a reliable source of interpretations out of it. Messenger is one of Urbaitytė’s conceptual abstractions created in acrylic paint on canvas, which was presented as part of the artist’s exhibition titled Choices (curator Elona Lubytė, National Art Gallery, 2012).

UždarytiThe painting is paradoxically self-contained. The image is abstract and neither letters nor numbers that are part of the painting’s composition help to unravel its meaning. It might sound strange, but it seems that Messenger does not carry any message.

This particular abstraction by Urbaitytė was created in the 1970s, during her New York period. It was the time when the artist’s career was in the ascendant: she held several solo exhibitions, and her artwork was exhibited as part of a female artist exhibition held at the Brooklyn Museum and was shown at the American painters’exhibition in Paris (1975–1976). It was a great success, because, according to the artist herself, at that time there were around 60,000 artists creating art in New York.

The elegant dark-haired lady in the photographs vigorously posing in the encirclement of her geometrical paintings is Elena Urbaitytė, a New York artist, school teacher of art in Long Island, Bachelor of Arts from a college in Alabama, and a graduate student of the famous US painter Will Barnett. She was highly intellectual. Her extravagant appearance was a mere cover and her way of hiding her internal drama both from herself and from others. During the war, all of a sudden she found herself separated from her family and from Lithuania. Her father was tortured and perished in Soviet forced labour camps. Her brothers and mother stayed in Soviet Lithuania and their relations did not become any warmer even after they finally met. Urbaitytėfound a colourful way to describe it in her memoirs The Punished.

Her manner of painting is impersonalised as if attempting to objectivise the creative process and to avoid any direct mental self-expression.

Most probably the fact that she realised her loneliness in the world so early in her life, including the need to do something meaningful in life, told on the artist’s creative life, which, as a result, appeared to be rational and fragmented, not scattered, but rather confined in a construction made of the artist’s iron will. This is why it is rather logical that Messenger does not carry any message. It remains hidden especially from those who are looking for traces of the ‘Lithuanian tradition of art’ in her artwork or, to be more exact, do not see further than the European tradition of expressive art.

Urbaitytė is a product of the West, the bubbling melting pot of art life in New York and the American concept of art: ‘Being free from obligations to the European culture, they rejected and denied the thesis that art has anything to do with the issue of beauty.’(Barnett Newman)

This artist, unlike the majority of other Lithuanian expatriates, adapted and grew into the environment of American art. Her personal strategy (determined by the American tradition of art and her traumatic past experience) was to hide behind the art that she created rather than to open up through it. Her manner of painting is impersonalised as if attempting to objectivise the creative process and to avoid any direct mental self-expression.

Without any reservations, Urbaitytė belongs to the Western world of art. Indirectly, she belongs to that narrow but fascinating circle of Lithuanian expatriate artists (Jonas Mekas, Jurgis Mačiūnas, Aleksandra Kašubienė), who embraced the West like an opportunity and a gift rather than an imposed burden.

This might well be the reason why the composition of Messengeris so inarticulate despite being so dynamic and bright. The boundaries between individual forms are clear and precise with characteristic shallow non-differential tones, which makes them look less like specific forms, but more like planes of colour. Planes of warm and cool red crowd together and intersect each other occasionally. They are marked with numbers and letters written with great precision, however, even then they say nothing legible. The artist concentrates on the key features of painting –colour, line and form. Exaltation and highlighting of the features is, actually, what makes their content.

Nonetheless, towards the end I feel like giving in to a flow of free associations. I would say that Messenger, not the one who passes on a message, but rather an envoy or a herald –this logjam of forms –is a fragment of an airplane or a giant bus, which has been spotted from very close. Letters ACE-SET and WYZ are coded names of certain institutions that might actually be important for the passengers.

Without any reservations, Urbaitytė belongs to the Western world of art. Lithuania should be proud of this artist. Indirectly, she belongs to that narrow but fascinating circle of Lithuanian expatriate artists (Jonas Mekas, Jurgis Mačiūnas, Aleksandra Kašubienė), who embraced the West like an opportunity and a gift rather than an imposed burden.