Painting as a battlefield

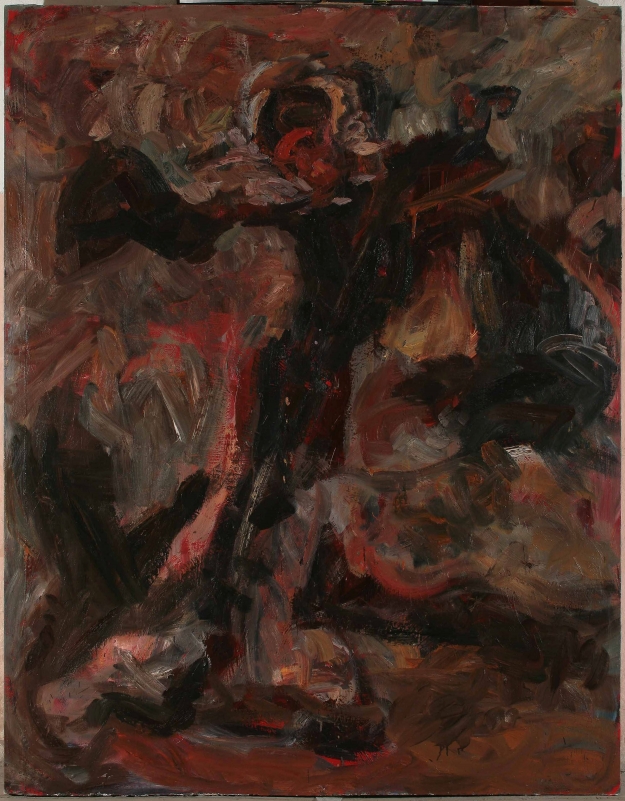

Sigita Maslauskaitė’s (b. 1970) painting Saint George is created in dark colours and heavyweight brushstrokes. It takes more than one look to understand what is portrayed in it. And once you understand that it is an image of a saint, you may be perplexed: is there really someone painting saints nowadays? Nonetheless, it is only at first sight that this piece of art might look like an exhibit from a boring museum hall.

It is rather difficult to perceive Maslauskaitė’s artwork unambiguously, because there are many things in it that have a different or another side. Even the purely physical contrast looks really interesting: massive paintings and a slender author with a light smile on her face. The deeper you go, the more interesting it gets.

The paintings that are so close to traditional expressionist art are created by an extremely active woman who successfully combines art and science. After graduating from her studies in painting at Vilnius Academy of Arts, she spent three more years at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome where she studied ecclesiastical heritage. Upon returning to Lithuania, the artist defended her doctoral thesis in art history and at the same time actively contributed to the process of establishing one of the best museums in Vilnius – the Museum of Ecclesiastic Heritage, which she now heads. In addition to all this, Maslauskaitė writes articles, curates exhibitions, gives lectures and paints consistently, even though not very intensively.

Here the biographic context appears to be really important. It shows that the traditional way of expression in painting that stems from the mid-20th century was her conscious choice rather than an imitation of the only known path.

Here the biographic context appears to be really important. It shows that the traditional way of expression in painting that stems from the mid-20thcentury was her conscious choice rather than an imitation of the only known path. It must be noted that it was a rather unpopular choice, too. This kind of painting reminds of museum exhibits and is difficult to reproduce. Paper or screen does not convey the size of her works, the facture of the thick layer of paint and even emotion. The topic of her paintings is rather inconvenient, too. Maslauskaitė’s paintings are often based on religious plots which scare away non-religious viewers, and quite unnecessarily so, as we will soon witness.

The plot of the painting Saint George is no exception. Religious subjects dominate Maslauskaitė’s artwork. When speaking about her choice, she avoids spiritual romantics:‘Most probably, all the characters –angels, jeronimos and georges –are a result of my studies in iconography, doctoral thesis and ecclesiastic stocktaking. But the moment I say it, I want to deny it right away, because, first of all, it is scary to paint saints (all the masterpieces have already been painted), and second, I have seen so many bad modern paintings on religious subjects that I feel the urge to avoid iconography altogether. Most probably the best way to put it would be to say that I am simply painting and familiar characters emerge in the process. I do not create them on purpose.’

"Most probably the best way to put it would be to say that I am simply painting and familiar characters emerge in the process. I do not create them on purpose."

Standing in front of a two-metre high painting feels like a confrontation in a combat. Maslauskaitė wrestles with paint and spreads one layer after another in an absolutely‘unladylike’way to have figures and new colours emerging from her thick brushstrokes. It is obvious that the portrayed figure is fighting fiercely too, but its enemy is not clearly visible. When we hear about Saint George, the image of a dragon, an inseparable iconographic attribute of the saint, comes to our mind right away. The plot is popular and the funny small dragons, just like the formidable giant dragons in the old paintings and frescos, always bring a smile to the faces of viewers.

Maslauskaitė’s saint is fighting today, in this very moment, therefore, it is fighting an abstraction. The efforts of the character can be sensed from dynamic movements of the portrayed figure, all the brushstrokes that come out in sinister puffs and the colours of the painting that remind of a night lit by the flames of fire. It is not quite necessary to remind ourselves that it is a saint when admiring the figure of the character in the painting. It could as well be a mere image of a troublesome sleepless night or that of a day when you fail to understand what is actually happening around you.

No matter whom we decide to identify the portrayed figure with –a saint or our own self –it simply continues to radiate energy and tell about a motion that might never end. From time to time indescribable flashes of light penetrate the dark. Here and there multicolour shades are interrupted with pure colours and the brushstrokes continue to whirl in circles as if in a never ending battle. Or in real life.