Before pressing the button

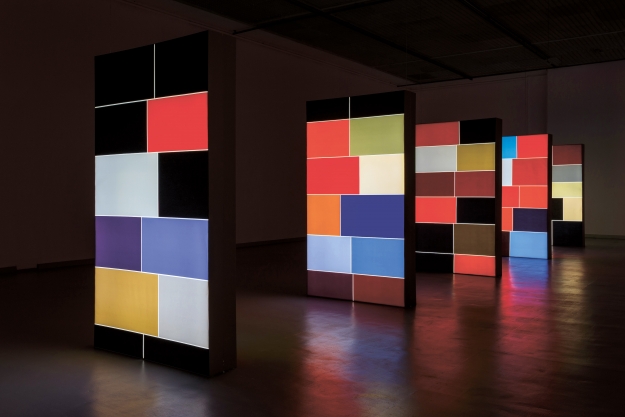

This is already the third work by artist Indrė Šerpytytė (b. 1983), who lives in Great Britain, which I have happened to see. The first one was made of photographs of objects suspended in the dark and spoke about the mysterious death of her father (A State of Silence, 2006). The second one contained three pieces of research into post-war stories and related memories captured amid the dates inscribed in the title of the artwork (1944–1991) (2009–2015). The third one is titled 2 Seconds of Colour (D). The topic of trauma or, to be more exact, the tension between the knowing about what happened and the perception that it is impossible to experience it from a distance, connects the three different works. This time the artist conveys the state of being perplexed which is expressed with the help of five parallelepiped rectangles, all lined up in a dark hall and reminding of soviet block-buildings with lights in their coloured windows. Such abstractions, the artist’s statement says, emerged for a couple of seconds on her computer screen when trying to open photographs of ISIS executions. All that was visible on the screen was the dominant colour of the image. Thus, the artist turned the glitch – the digital code of system error – into a question.

UždarytiThe work can be admired as a beautiful abstraction – a reply to Piet Mondrian from the 21stcentury. However, when examining the monoliths the viewer hears the voice of Eleanor Margolies ‘describing’ the photographs. All of the descriptions sound very much alike: desert sand, blue sky, the executioner dressed in black, his eyes are impossible to discern, he is looking sideways with his head bent to one side, he is holding a weapon in his outstretched arm; a man in orange overalls is either kneeling or standing, the blade of the knife is at his throat.

Some of the photographs depict a scene after an execution where the bloody head of the victim is placed on the back of the dead body which is lying face down. However, even in that case the verbal description of the image would have a soothing effect, because the narrator mentions every single detail in the picture, every irrelevant minor thing, including the curve of the back and a bird passing by. As a result, the listener’s perception is slowed down and diverted, whereas the image strikes you right in the face, just like the monolith constructions by Šerpytytė.

Thus, the glowing colourful blocks and the description of images both supplement and seemingly contradict each other. Still, not a single segment of the artwork ‘knows’ the actual truth. The voice changes the meaning of the ‘innocent’ rectangles by encouraging the horror in them to be discerned and creates the time space of the event in the current moment where I am standing now. In the meantime, the monoliths expand the statement and turn it into a reflection of all times, of all crimes, sufferings, sacrifices and salvations of the man like obelisks made of glass.

ISIS arranges executions as if they were performances devoted specifically to Westerners. They have found an intelligent way to use the aesthetics of the Hollywood movies, popular Western magazines, sports events and computer games for the purpose, including the way visual delights are combined with the need to excite oneself at the sight of somebody else’s sufferings when sitting comfortably in one’s chair.

Those who live in the realm of art may perceive abstraction as something more eloquent than a painting with a specific narrative, because abstraction contains theory.

The contrast between the orange overalls of the victim-prisoners and the black clothes of the ninja- executioner-heroes becomes stuck in our memory like logos conveying a corporate mission and continuously irradiating us on the internet. For someone like me, all these things seem to be just as forbidding as all the exhortations to believe the consumerism ideology or any other post-truth created with the help of design, high-sounding phrases and hyper-realistic photographs. However, some individuals will look like they have been drawn into a virtual reality game, where every loser can turn into a hero. Maybe this propaganda works so well because all media, cinema and advertising channels pressurise us to be special, but all that the real world is able to offer is a ‘terrorist’ job in telemarketing or a place in a queue for a free lunch. I have difficulty imagining myself in the place of the executioners, but it is extremely easy to imagine myself in the place of a poor individual who was raised to imagine himself a hero.

I think that the monoliths glowing in the dark are a perfect expression of the postmodern sublime. Jacques Derrida and François Lyotard locate the feeling of the terrible, the infinite and the indefinable at the frame of a painting that marks the unrepresentable, the threshold to infinity, on the other side of which there is nothing but an abyss. On the level playing ground of the usual scenery, this kind of artwork destroys the illusion of delightful existence and leaves a crack which stays open like a wound, a non-healing contradiction in the mundane life which is prone to conciliation, adaptation and conformism.

Most people who do not have much to do with art perceive abstraction as something silent, because there is nothing in it that they would recognise, and there is no story in it. Those who live in the realm of art may perceive abstraction as something more eloquent than a painting with a specific narrative, because abstraction contains theory. It is not by accident that Lyotard considered abstractions by Kazimir Malevich and Barnett Newman to be examples of art expressing the sublime: a thin line cutting through a coloured plane and a white square ‘allowing to see only by making it impossible to see’ (Postmodern Being). In the culture of the second half of the 20thcentury the Holocaust became something to be remembered, but not to be shown. Nowadays we notice a global increase in violence which is becoming too much for our minds, overloaded with visual and oral information, to accept. Again, maybe the only way to express our horror that there could be another holocaust is through abstraction, because by exhibiting the impossibility to express, it encompasses all the violent experiences that do not go together with all the great stories that are being voiced – again – from high-ranking posts.