The small sacred sanctuaries

The development of the non-figurative art was not finished with Kazimir Malevich’s disruptive Black Square (1913). Abstract painting proceeds its development to this day. In Lithuania, abstractionism is often associated with Kazė Zimblytė (1933–1999). When the art of painting shed its historical duty to represent reality, an exciting space for play and research emerged that revolutionized painting beyond recognition. Artist Kazė Zimblytė made the flat space of painting her experimental playground but she did not focus on the force of expression, did not attempt to overwhelm viewers with dramatic effects; on the contrary, her works are increasingly sedating, made of solid elements. Simultaneously the connecting links between the elements are subtle, refined and loosely integrated. These are fragile structures where mere tingles in colour are enough to manifest vivid changes on a flat space.

UždarytiZimblytė’s contemporaries knew of and appreciated her works but not the official Soviet authorities. She graduated from Vilnius Academy of Arts in 1959, with a specialty in textiles. After that she created design for fabrics in textile factories and her work was highly regarded. Later she worked together with architects but was drawn into art. Eventually Zimblytė decided to abandon working with industry, and joined the Lithuanian Artists’Association and devoted herself to high art. Her husband Vincentas Gečas, the rector of Vilnius Academy of Arts at the time, supported her decision but shortly after they divorced. This put Zimblytė in a difficult situation.

The first exhibition of her works was organized in Vilnius, in the Vaga Publishing House hall of events. The exhibition was given a remote part of the hall rather than the central space; notwithstanding, a day later Soviet officials slammed the exhibition and immediately closed it. The artist became undesirable at official exhibitions. Even semi-public spaces such as Vaga Publishing House were closed to her. Zimblytė was effectively blacklisted and could not exhibit her works. But soon afterwards she was noticed by some Moscow underground intellectuals. Anatoly Strigalev, an art critic, became her patron and arranged for her works to be exhibited in the private Vasily Rakitin gallery in Moscow and showed them to buyers of avant-guard art in the Soviet capital.

Zimblytė takes coarse basic elements, such as matter and time, and creates an eternal move that invites to be noticed. Thus, the artist reconciles an instant and eternity on a flat surface.

In 1973, Zimblytė was commissioned to create the curtain for Moscow’s Genessin Academy Theatre. According to the design of the artist it was to be a patchwork picture composed of light-brown, orange and terracotta coloured squares sewn on a backing material. The artist was impulsive, spontaneous and immersed in her creative process and never focused on the technological aspects of her designs. Perhaps this was why she failed to take into account that the curtain might not withhold its own weight. Indeed, it tore during the opening and had to be restored.

Soon after Kazė Zimblytė returned to Lithuania and struggled to make ends meet. Official authorities would not endorse her, so she could not enter exhibitions. This meant she had to exhibit her works in the house of Judita and Vytautas Šerys. She performed installations with rice paper stripes in her native homestead in Briedžiūnai, Ukmergė County, and in Jeruzalė district of Vilnius –on the meadow near the house of Marija and Vladas Vildžiūnas. Although her works were first exhibited in 1959, Kazė Zimblytė only had her first solo exhibition in 1988, when the end of the Soviet regime was in sight.

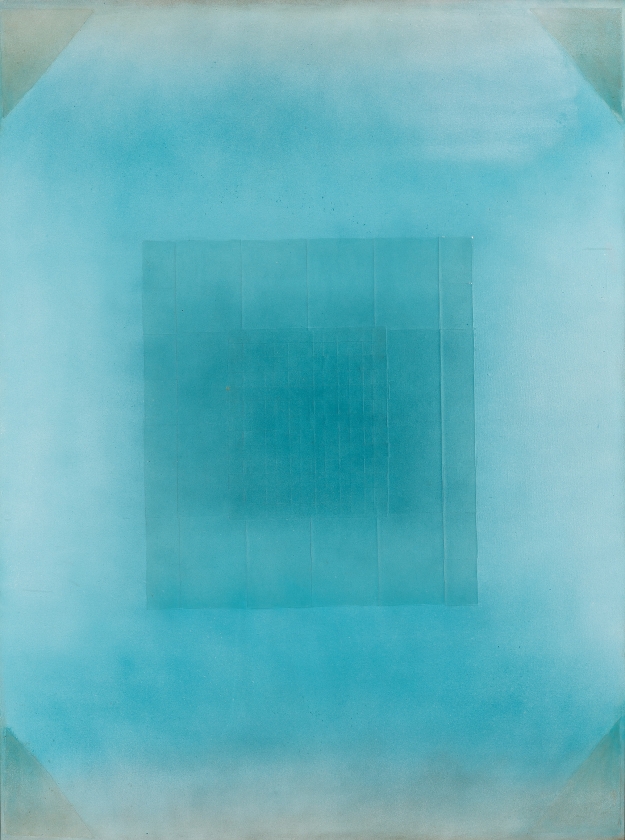

People who knew her confirm (or one can see that by simply looking at her works) how much she appreciated colours. Zimblytė creates her world of dull and down-to-earth dark-brown, navy blue and green juxtaposing them with heavenly light blue as if designing her painting to be part of nature. Oftentimes she adds subdued gold or silver penetrating through the layer of other colours or reaching from the background surface of the painting. In both cases, it provides the impression of dimmed light emanating from a sublime source. The artist is mindful of the slightest nuance, even of half-tones. These nuances are Zimblytė’s solid building blocks to construct her abstract compositions as small sacred sanctuaries weaved on the flat surface of the paintings.

The flat surface is but an important tool to project imagery liberated from the duty to reflect reality. Here the surface is little short of a solo party in terms of its importance and is employed to work with colour closely. Zimblytė uses collage to create additional flat surfaces –which can be made of pieces of metal or simply rag paper to make a rougher background structure. Such tools of expression are enough for Zimblytė to establish an art world to draw our thoughts to metaphysical reflections. Pieces of paper displayed in a homogeneous rhythm in the centre of the painting sometimes have jagged edges as if time has taken its toll on them. They emanate in the light of early evening and playfulness of tree ring curves which we internalize with ease, without verbalizing our sensations. The artist combines what seems irreconcilable: rhythmical systems are created of mostly rectangular elements. Hard-angle signs so prevalent in our world are mysteriously transformed into soft and vibrating art. Zimblytė takes coarse basic elements, such as matter and time, and creates an eternal move that invites to be noticed. Thus, the artist reconciles an instant and eternity on a flat surface.